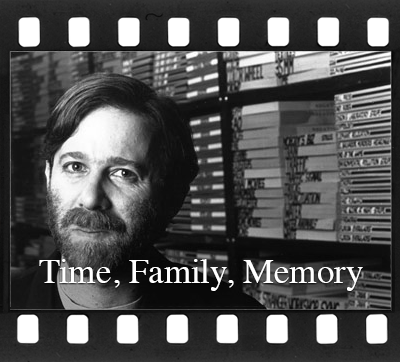

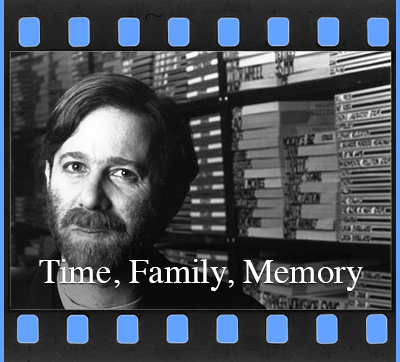

Alan Berliner's Acceptance Speech

San Francisco Jewish Film Festival Catalogue Statement

July 29, 2013, Castro Theater

I want to first thank Lexy Leban, Jay Rosenblatt, and everyone else at the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival for selecting me as this year's recipient of the Freedom of Expression Award.

I am profoundly honored, I am profoundly grateful, and I am profoundly humbled to join the esteemed group of filmmakers – including Jay himself -- who have stood here before you on this very spot, in this magnificent room – to accept this profound gesture of affirmation and support. Ever since I received word that I would be this year’s honoree, I’ve been pondering how to make sense of it. How to connect my little corner of the independent filmmaking universe with the far-reaching, and truly inspiring human-rights implications of the phrase “freedom of expression?

And truth be told, before my recent trip to Turkey a few months ago, I would have answered that question quite differently. I am after all, as Jay said, someone who has felt free to use my own life, and the lives of those I know and love – my family -- as an elaborate laboratory in which to explore the rich intersections and ironies of family, family history, personal memory, the construction of identity, the horizon of mortality, and the unspoken power of family legacy. Etcetera. I make personal films, and when I do it right (and I don’t always do it right), I’m able to translate – to express – all of that detail and specificity -- all of that intimacy -- into films that hopefully make you the viewer reflect upon your own family, your own family history, your own memory, identity, mortality, and the unspoken power of the family legacies that shape who you are and what you do. Etcetera. And I’d like to think I’ve done so in ways that challenge and stretch the traditional forms of documentary storytelling; I’m someone who believes that the way I tell a story should be as interesting as the story I’m telling. Okay… Fair enough…

But back in late May and early June I found myself on the streets of Istanbul, Turkey at the cusp of an extraordinary time for the Turkish people. I was a first-hand witness to the sights, sounds, and indescribable energy of thousands upon thousands of Turkish citizens learning how to pronounce, how to declare, and ultimately how to exclaim their own collective freedom of expression.

On more than one occasion I learned first-hand just how effective tear gas is at dispersing crowds – and at bringing you to your knees. To make one very long story short, I can tell you that at one point on the early evening of May 31st 2013, I found myself running as fast as I can, stumbling, trudging, and then crawling in slow motion, before coming to a sudden stop, frozen in my tracks on a narrow cobblestone street. Forget about the fact that I couldn’t open my eyes; my lungs were burning so intensely that I could barely breathe, and I thought I was going to die.

I’d never had to run for my life before. I‘d never been in such direct confrontation with the raw, brazen power of the state. Then again, I’d also never experienced the urgency with which the citizens of a city, of a country, of a society challenged the very foundation of their social contract. Where people were willing to risk their lives for the freedom to express themselves.

I had been invited to Istanbul to present a complete retrospective of my films – most of which was cancelled -- and also to give a master class, which ultimately did take place – albeit on a different day, at a different place and at a different time. But given the utter urgency of the situation, it didn’t make much sense for me to talk about how I make films about my family, my family history, my name, my insomnia, or the unspoken power of my maternal grandfather’s legacy. Etcetera. And so when I finally met with the film community of Istanbul – I found myself talking about the importance of bearing personal witness to history. I encouraged everyone in the room to find their own personal relationship to the bigger picture; to push through the boundaries of their fears and anger… to see through the tear gas, the water cannons and the rubber bullets – so that they might help one another – and the rest of the world – understand, appreciate and remember -- the meaning of the social and political turmoil that was engulfing their lives. That the films they would make now would be their legacy to future generations of the Turkish people. Etcetera.

Now I’m not here to tell you that I’ve suddenly become a revolutionary, and that my next film will be about Istanbul, Turkey, or Alexandria, Egypt, the place my mother grew up – and another city (and country) in extreme crisis. But I am here to say that I was quite shaken by my experience in Turkey, and that I’m somehow different because of it.

As you can probably tell, I’m still chewing on all of this. The truth is, awards and honors aside, I’m still learning how to do this thing called filmmaking. I’m still struggling to understand what it means to be an artist in our part of the world, at this moment in history, in this day and at my age. I’m still grappling with the far-reaching implications of my own freedom to express – and what a power it is, what an opportunity it is, and what a responsibility it is.

So there you have it. I went to Istanbul to give a master class, and somehow it feels like I’m the one who learned the most. How Jewish is that!

- ◻ CATALOGUE STATEMENT

- ◻ CATALOGUE ESSAY BY THOMAS LOGORECI

- ✓ ALAN BERLINER'S ACCEPTANCE SPEECH

- ◻ J WEEKLY