A Genealogy of the World

Alan Berliner Film Retrospective

International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam

2006

Catalogue Essay by Dana Linssen

This year’s top 10 documentary classics from film history were selected by American filmmaker Alan Berliner. A large part of his work will also be screening at the festival, including his latest piece, Wide Awake. Berliner makes highly personal films in which, alongside found footage and archival materials, he himself and members of his family often play a leading role. Strangely enough, this results not in sugary intimacy, but rather in an all-encompassing, almost universal oeuvre.

The largest genealogical archive in the world is held in a nuclear bomb-proof shelter in Salt Lake City. Even if planet Earth dies, this will preserve a record for all eternity of who was related to whom in this terrestrial life; a tremendous, but worrying thought. Isn’t this exactly what we all want, for traces of our existence to be left behind after we are dead? Isn’t this why we spend our lives busily being explorers and treasure hunters, archaeologists and private detectives, in order to define ourselves philosophically, psychologically, scientifically, artistically and practically? Is it just to leave something behind? Who am I? And why?

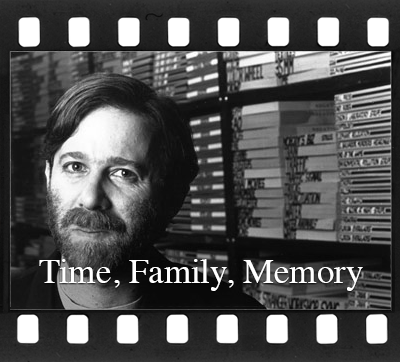

In what is probably his most well-known film, Nobody’s Business from 1996, we see American filmmaker Alan Berliner (Brooklyn, 1956) searching through this safe in Utah, looking for information on his family. Berliner’s master plan is possibly even more audacious than that of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which maintains the database and which sees genealogical research as a bequest to eternity. Berliner compiles a film archive showing not only the relationships between fathers and sons, grandfathers and grandchildren, but also in which everything is related to everything else. Seriously everything. Berliner is a builder of systems, in the same way that the heavyweight philosophers or theoretical physicians work on “theories of everything.” Except that the building blocks of Berliner’s theories are not “being” and “non-being” or electrons, protons or even smaller elements (well, they are a bit). His cosmology is principally concerned with what connects lions to trains, Egyptian cotton to Eastern-European Jews, Japanese kimonos to insomnia and scientific information films tothe most beautiful thing in the world: the sound of your own name. He has even made a whole film dedicated to the latter: The Sweetest Sound (2001).

Flea market finds

His first student films in the 1970s and 80s are also based on visual association, using his collection of found footage, which was already growing at a steady pace in those days: from news footage to nature films, unidentified fictional film fragments to almost abstract visuals from industrial processes, all of which had a great affinity for the interplay of order and chaos, simultaneous deconstruction and reconstruction. One great homage to the marvel of editing: how it is possible to bring together seemingly unconnected, random images and sounds, and allow them to collide like atoms in a vacuum, thereby giving them meaning, even creating something new, something previously undreamt of.

In the 1980s, Berliner discovered the home movie as an inexhaustible means of further exposing the relations that exist in the world. A process that started off innocently enough, with The Family Album (1986), a collage made up of film material found at flea markets, covering the 1920s to 1960s; two generations of American family life. Alan Berliner is a filmmaker – but is he a documentary maker, because he documents the world? Or should he be placed in the grander tradition of essayists, participating researchers, poseurs and collectors who also commentate on this world by putting a telescope lens in his microscope, or vice versa? With Berliner, every focus on the micro opens up a much broader horizon for understanding the fundamental questions of life. Likewise, every glimpse of the big picture can only be understood within his cinematic metaphysics by entering into a personal relationship with it.

Flamboyant grandfather

In the editing suite of one-man film army Berliner (lights! camera! action! editing!), these fragments, at first glance just highly private records of holidays and birthdays, become evidence of the fact that we always act differently in front of the camera than how we really are. But what if our self-chosen representations were all that was left of us? What then? Could it then ever be possible to understand something of humanity? Was it ever possible to, objectively, understand anything at all about human beings?

It was inevitable that these questions would lead to the celluloid diptych at the heart of Berliner’s oeuvre: the portrait, made up of his own family’s home movies, of his flamboyant grandfather Joseph Cassuto (Intimate Stranger, 1991) and the portrait of Berliner’s father Oscar, a man who rebelliously wondered who in the world could possibly be the slightest bit interested in his totally ordinary life (Nobody’s Business). These are personal histories that reflect the entire history of the world and have earned Berliner the nickname “the Woody Allen of the documentary”. Films that raise the question of whether you can really reduce a human life to the hereditary material contained in a single cell, while at the same time confronting us with the fact that, however painstakingly you go to work, collecting everything, talking to everyone, there will always be blank areas, blind spots and unexplored corners in any biography.

Maniacal

This is why Alan Berliner’s films are also about the metier of documentary making itself: about the fact that it is impossible to make an objective report on reality, but equally impossible not to carry on trying to do so, with almost maniacal, meticulous zeal. This is also the big difference between Berliner and many filmmakers who, in reality, scour flea markets for material with which to cobble films together or, for lack of any better stories, point their cameras at their fathers. In the case of Berliner, it is always the better, bigger story that keeps the compass pointing to home. It is always the all-encompassing story of humanity that can only be told by zooming in on the eyes of an unknown child from a discarded film; because these eyes are a window to the world, just as much as any others.

Enchanting universe

In his latest film, Wide Awake (2006), Alan Berliner brings us another step closer to the how and why of it all. On the surface, this is a hilarious film about insomnia, but at the same time there is a not completely scientific laboratory atmosphere, allowing free-roaming investigations into issues such as inspiration, creativity and the meaning of existence, what your parents have to do with it all, and which came first, the chicken or the egg (does Berliner not sleep because he is a night person, or is he a night person because he can’t sleep?), and why someone who sees editing as the greatest of the filmmaking arts, can’t tell himself to “cut.” In Wide Awake, Berliner gives the audience a glimpse of his personal sound and image archive, which – unlike in Salt Lake City – does not contain information on all Berliners and Cassutos, neatly in alphabetically ordered microfilms, waiting for eternity, but rather in which Reagan follows Rain and Volcano Violence and Vietnam; a seeming order, and a desperate attempt to impose structure on the flux of life. But it is between the missing headwords that the glimpses, the flashes of insight are to be found. Behind the casual, futile façade disguised in the found footage images lies an enchanting universe of unshown, hidden truths and realities.

Dana Linssen is film critic for NRC Handelsblad and editor-in-chief of de Filmkrant

- ◻ BIO

- ◻ WIKIPEDIA

- ◻ IMDB

- ◻ The Gift of Time

- ✓ A Genealogy of the World

- ◻ PHOTOS