American Family Life Whittily Revealed

by Phillip Lopate

New York Times

Arts & Leisure

Sunday, January 12, 1997

In this age of memoir, when, thanks to simplified technologies, everybody’s life becomes potential movie material, documentary film makers all over America have taken to mining the stories of their immediate families. But a gulf separates those myopic, sentimentalized or resentful family chronicles from a handful of truly well-made documentaries.

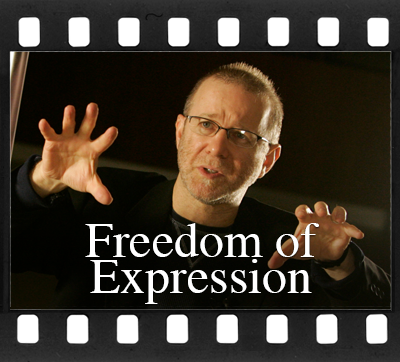

No one has been more dogged or more successful than Alan Berliner, whose trilogy of feature documentaries will be shown tonight, Tuesday and Thursday at the sixth annual New York Jewish Film and Video Festival at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center.

Mr. Berliner’s first feature, "The Family Album," made in 1986, consists of found home movies and audio tapes that are edited together to tell the story of American family life. While the images celebrate, as home movies tend to, the optimism of social rituals, holidays and horsing around, the voices on the soundtrack often tell a troubled story.

In his second feature, "Intimate Stranger," Mr. Berliner focused on his maternal grandfather, Joseph Cassuto, an Egyptian-Jewish cotton merchant who ended up working for a Japanese firm and living away from his family 11 months out of the year. Cassuto comes across as a hero to his Japanese colleagues (to whom he sent food and medical supplies after the war), a good-will ambassador to the world but a stranger in his own household.

"I never me anyone who didn’t like him — outside of his immediate family," says one son.

Yet Cassuto’s daughter Regina, the filmmaker’s mother, continues to idealize her father. We are left with a complex portrait of a man who had a talent for friendship but was weak in the domestic areas. The film maker presents conflicting judgments of his grandfather, who died when Mr. Berliner was a teenager, but abstains from passing judgment himself.

In his most recent and most powerful film, "Nobody’s Business," Mr. Berliner, who is 40, does not have the option of detachment because this time he has made a film about his own father.

"You have one bad habit," Mr. Berliner’s father, Oscar, admonishes him in the film. "You think if something’s important to you, it has to be important to everyone else."

Oscar Berliner, a retired sportswear manufacturer who has entered a brokenhearted, reclusive old age, resists mightily the idea that he is a worthy subject of a motion picture. "I’m just an ordinary guy; my life is nothing," he insists.

Recurring clips of prizefighting wryly comment on this duel between stoic, clamlike father and stubborn, prying son. Oscar Berliner was a perfect 40’s man, a solid, hard-working, honorable guy who fitted in best with his army buddies during World War II. Then he married the glamorous, exotic, aspiring actress Regina, with whom he was classically mismatched. "We crossed paths in a head-on collision," Regina comments in the film. "He was ready to get married, and I was ready to leave my father’s house." The film maker’s sister, Lynn, who provides a balanced, sympathetic voice, says: "He married the wrong woman. End of story."

Yet Oscar Berliner, this seemingly defeated old man who is now in his late 70’s, keeps surprising viewers with his combativeness and the integrity of his indifference. When the filmmaker tries to interest him in research about their ancestors, Oscar dismisses it as phony nostalgia.

"There was one tombstone standing all alone, and that one I chose to see as your grandfather’s," Alan Berliner tells his father.

"Hooray for you," comes the sarcastic reply.

It’s a measure of the filmmaker’s generosity that he lets his father win his share of the arguments. Yet his father also catches us off guard when he dotes on his new grandchild; this is a man, after all, whom we have been told can no longer love.

"There’s a general sense that Alan Berliner has figured out the family documentary form," says Jack Salzman, media director at the Jewish Museum, a sponsor of the event. "He really does explore family relations in an energetic, vital way. Alan manages to impose his presence and voice on the film, without getting narcissistic."

How do Mr. Berliner’s explorations manage to evade the pitfalls of the family film? For starters, they are dramatically tight (each no more than an hour long); they are full of juicy conflict and contradiction, innovative in their cinematic technique, unpredictable in their structures, and they spring from a high degree of preliminary analysis. This is cooked, not raw, material.

"Alan Berliner represents to me the most exciting breakthrough out of the impasse of the family film," says Richard Peña, program director of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, another sponsor of the Jewish Film Festival. "Most documentaries end up planting the camera waiting for something to happen. With Berliner, one sees a much more playful, essayistic thought process at work."

Mr. Peña compares "Intimate Stranger," with its own multiple contradictory narrators, to "Citizen Kane." Mr. Berliner agrees that "Citizen Kane" was an influence. The point is that Mr. Berliner’s storytelling may have more in common with the subjective psychology of characters in fiction films than with the traditional documentary’s display of fact as objective truth.

Commenting on Joseph Cassuto’s seemingly nutty habit of writing Presidents Kennedy and Nixon with offers to advise them on matters of state, one relative says: "Look, Alan, you live in your head; he lived in his head. In his head your grandfather saw himself as a statesman." The wounded patriarchs of these two last films are, in different ways, solitary men isolated in their minds.

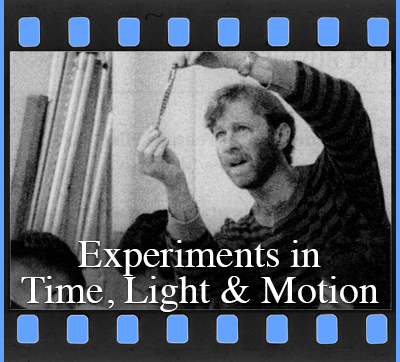

Mr. Berliner himself is a thin, bearded, gentle-voiced, slightly formal man whose nervous laugh seems a warning of the stubborn will lurking underneath. He lives in a TriBeCa loft with his wife, Anya. His extensive collections of photographs, family films and notes are archived with a neatnik’s color-coded obsessiveness.

Mr. Berliner, who was raised in Far Rockaway, Queens, was trained as an experimental film maker at the State University of New York at Binghamton. His early shorts were all geometric, structuralist. "The idea that I would someday make a film outside a minimalist, abstract vocabulary was implausible," he says. Then humanism struck. He found himself making highly accessible, emotionally gripping, narrative work.Mr. Berliner, who was raised in Far Rockaway, Queens, was trained as an experimental film maker at the State University of New York at Binghamton. His early shorts were all geometric, structuralist. "The idea that I would someday make a film outside a minimalist, abstract vocabulary was implausible," he says. Then humanism struck. He found himself making highly accessible, emotionally gripping, narrative work.

Yet there are traces of the experimental film maker in Mr. Berliner’s style, like the device of using images and sounds of a manual typewriter to help structure "Intimate Stranger" or the boxing ring that becomes a leitmotif for "Nobody’s Business." The experimental training also surfaces in the abundance of techniques employed, as well as a playful soundtrack, which avoids a literal connection with the visuals. For instance, while his estranged parents are each telling about their marriage breaking up, we see not their faces but footage of a hurricane-swept house falling into the river below.

Mr. Berliner compares hovering over a Steenbeck editing table to sitting at the Steinway. Having made his living for years as a sound editor, he continues to be a film artist for whom editing is central. "Editing is constructing and articulating a flow of thought," he says, and a "flow of thought" is one way to define Berliner’s films.

THE FAMILY TRILOGY (the last two of which were shown at the New York Film Festival) follows a trajectory of increasing vulnerability from the relatively impersonal "Family Album," in which the voices of Mr. Berliner’s family (among others) are heard but never seen, to "Intimate Stranger," which has no on-screen dialogue, and finally to "Nobody’s Business," with its no-holds-barred encounters. What next? Will he make a film about himself? Mr. Berliner is unsure what his next project will be, but feels he is still too young to make an autobiography.

What of the emotional pitfalls of working with one’s family as primary material? Hurting the feelings of loved ones? When Mr. Berliner’s mother asked him why it was necessary to include unflattering aspects in his portrait of his grandfather, he told her he was trying to get a fuller understanding of who this person was. In his journal, however, he recorded his doubt: "Who am I as his grandson to burst into these sacred places and start rushing about making trouble, causing tears, opening wounds, exposing scar tissue and raising the dead? My uncle Al said he had a love-hate relationship to this project. That’s the appropriate tension for all of us."

Regina Berliner, the film maker’s mother, revealed another sentiment. "The films were very touching," she said. "I was in tears in some parts. Perhaps I would have liked to see the films first and edited a few things out. I ask Alan, ‘Why must every part of my life be exposed to the public?’"

"To make a good movie," he said. "I accepted it. I wasn’t very pleased, but I accepted it."

- ✓ NY TIMES 1/12/97