Watching Memories Slip From the Mind

Alan Berliner's 'First Cousin Once Removed'

New York Times

September 22, 2013

By JOHN ANDERSON

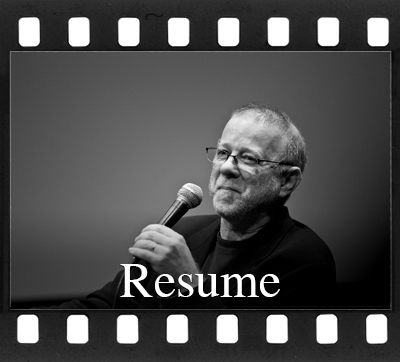

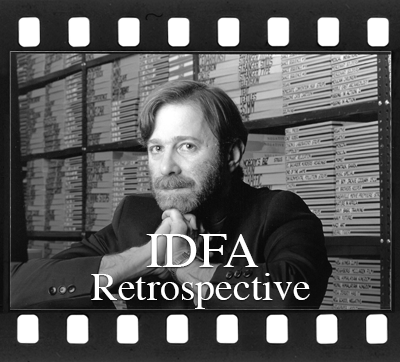

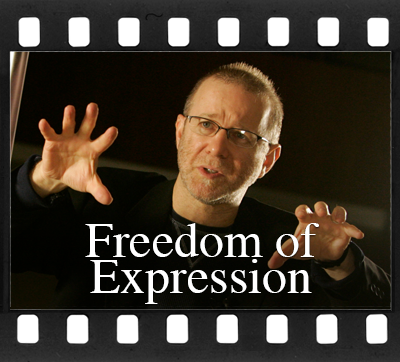

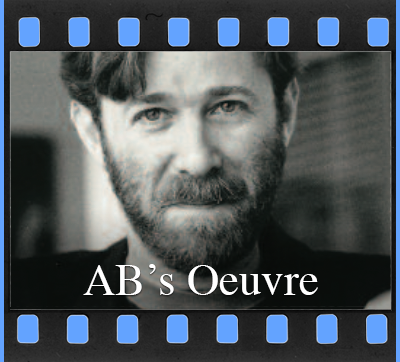

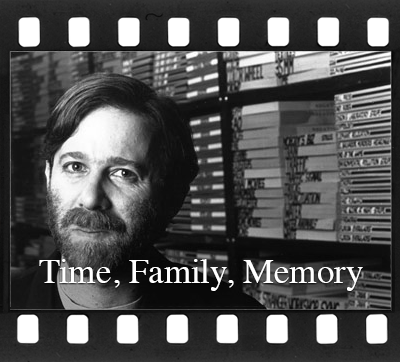

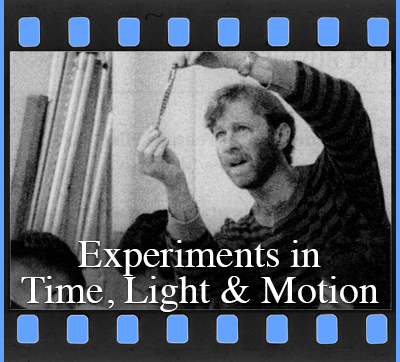

Robert Caplin for The New York Times

Alan Berliner at his studio in Manhattan. His new film, “First Cousin Once Removed,” documents the decline and the death of the poet and scholar Edwin Honig, his cousin.

Some years ago the documentarian Alan Berliner was going to make a movie about a California woman with superabundant autobiographical memory. “She remembered everything in her past,” Mr. Berliner said. “The neurologists studied her at UC Irvine for five years, and she was the real deal. No tricks. Extraordinary.”

The project didn’t work out, and Mr. Berliner sought solace in a familiar source. “I went to see Edwin,” he said, meaning his cousin, Edwin Honig, the renowned poet and translator, who was living in Providence, R.I., where he had taught at Brown University. “I told him I still wanted to do something about memory, and he said, ‘I’m worried about mine. Something’s happening.’ I said, ‘Can I bring a camera next time?’ ”

The result, “First Cousin Once Removed,” which opened this month in theaters before showing on HBO on Monday, is unlike anything he’s done before, Mr. Berliner said, although, as usual, his subject remained in the family tree. With “Intimate Stranger” (1991), Mr. Berliner explored the baroque life of his maternal grandfather; “Nobody’s Business” (1996), was about his father; “The Sweetest Sound” was about the name Alan Berliner and various Alan Berliners. The popular “Wide Awake” (2006) was a wry meditation on Mr. Berliner’s battle with insomnia.

“First Cousin” is many things at once: a family story, an Alzheimer’s travelogue and an example of nonfiction film as a vehicle for pure art. Mr. Honig, who died in 2011, may occupy the center of the movie, but the periphery is what its director chose to make it — a torrent of metaphor and imagery provoked, but not dictated, by the story of Mr. Honig’s departure from his past.

Mr. Berliner’s own past surrounds him at his work space in downtown Manhattan. Stacked on metal shelves that line two walls of the studio are hundreds of color-coded film cans and boxes. Red denotes black-and-white 16-millimeter footage; orange, sound; yellow, 16-millimeter color; blue, his family’s home movies; green, others’ home movies; violet, found photographs from around the world; gray, slides and transparencies. “It’s spectral, you see,” Mr. Berliner said.

Elsewhere along the shelves are subsections of emotional ephemera: discarded photo albums, love letters, suicide notes and journals, some found in flea markets, others in the trash. Cabinets are filled with wooden objects, pieces of carpet, flipbooks, toys, kaleidoscopes, zoetrope strips. Things for cutting. Things for pasting. Things for labeling. Things for measuring. A file cabinet is marked with the names of birds. Open a drawer, and the corresponding call rings out.

Then there are the boxes and boxes of newspaper clippings, photos, program notes, reviews. “I’ve freaked filmmakers out who’ve come to visit,” he said. “If they once had a screening at the Collective for Living Cinema and it was reviewed in the SoHo News by Amy Taubin,” he added, referring to the defunct theater, the defunct publication and the veteran film critic, “I’ll give it to them and they’ll say, ‘I don’t even have that!’ ” Would he describe himself as obsessive? Pause. “Of course,” he said. “I’m not afraid of that word.” He’s not always so fearless. “My father lost his memory at the end, as did his father before him,” Mr. Berliner said. “As I often say, ‘Do the math.’ ”

Mr. Honig was a cousin on his mother’s side. From that genealogical perspective, his studio suggests the interior view of one’s memories, preserved, one he drew on to create his cousin’s portrait.

Five years in the making, “First Cousin,” features the poet in various stages of descent into a cruel and incurable disease. “It was a big decision not to make the film chronological,” Mr. Berliner said. “I intercut, and by doing that I could create ironies and more complex meanings. Alzheimer’s might be a progressive disease, but it’s not a linear disease; you could be more lucid three months from now than you are today.”

Mr. Berliner received permission to make the film while Mr. Honig was still lucid, although he and his cinematographer, Ian Vollmer, both admitted to a certain uneasiness, inevitable given Mr. Honig’s deteriorating condition. “It was sometimes a wrenching thing to watch,” Mr. Vollmer said. “And it’s a disturbing film. When you’re in that condition, people would rather not look at you, they stop visiting, they don’t know how to handle it. It confronts them with the idea it may be them some day.”

The film is troubling in other ways, too. As a child, Mr. Honig was blamed by his father for the death of his 3-year-old brother, who was hit by a truck, though Edwin was just 5 at the time. When he died, Mr. Honig was estranged from his second wife and two adoptive sons.

“There’s a sense that, as we get to know more and more about Honig, all his great scholarship and creativity was really a shield against a world in which he was awfully unhappy,” said Richard Peña, who, as director of the New York Film Festival, programmed a 19-minute version of the film in 2010; the feature-length version had its debut at the festival last year. “The stuff with the sons is really heartbreaking, and some people were pretty angry about it, as they think it really tarnished his image.”

Reviewers noted the misgivings but largely praised the project: “Watching Edwin stumbling among the ruins of comprehension and expression, sometimes in a fury of frustration, is a humbling and often harrowing experience,” the critic Neil Young wrote in The Hollywood Reporter. “But it’s a worthwhile one, as Berliner crafts a quietly touching and illuminating memento mori from the steady dying of an intellectual light.”

Mr. Peña called Mr. Berliner “one of the great genre-confounders of our time.” He added: “I first knew of him as an experimental filmmaker, and now he’s often cited as one of our finest documentarists. Yet his style hasn’t really changed; I think he’s just forced us to reconsider all those definitions.”

For his part, Mr. Berliner said he considered Mr. Honig an author of the film. “Edwin says things that evoke images and thought processes in me all the time,” the director said, still speaking of his cousin in present tense. “I showed him a green maraca he’d used to play with my son Eli, and said, ‘You remember playing with Eli?’ and he looks at me and says, ‘I have no night of what I knew in the morning.’ I could try all day and wouldn’t come up with something like that.”

- ✓ NY TIMES 9/22/13