Patience and Passion

DOX Documentary Magazine

Autumn 1994, #3

My first few words, like the opening shot in a film, are intended to draw you in, to connect with you, to make you want to follow my thoughts through until the end. Whether it's an article or a film, our unspoken contract is still the same: you want to be informed, stimulated, challenged, fascinated, entertained, and/or moved by an experience that is both meaningful and well crafted. If I want to keep you here, my words, like the shots in a film, must be well edited.

In our own way, each of us is already an accomplished editor. We've learned to edit aspects of our daily lives in order to survive. We edit the clothing we wear, the foods we eat, the friends we keep. We edit the information we choose to digest from the glut of media overload that besieges us each day. We edit how we spend our time. These decisions, this idea of selecting, discerning and judging is ultimately about asserting some kind of organization and order in our otherwise unpredictable lives.

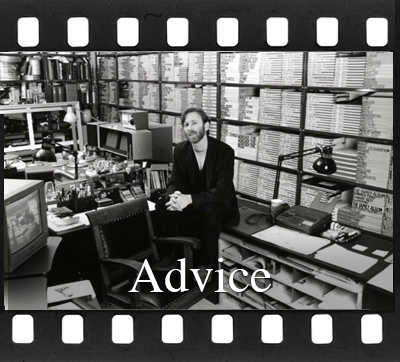

Inside the editing room, I can play God. If something doesn't fit, I change its shape. If something doesn't work, I try another approach. For me, editing is a kind of safe haven, a place where practice does make perfect. Well, not exactly perfect, but close enough.

The hardest part of making my own films is 'suffering the patience' required to absorb, internalize and memorize scores of hours of the myriad sounds and images that constitute my raw material. However eager I am to get my hands on the film, this initial if somewhat frustrating phase is absolutely essential; learning the material is harder than working with it.

An editor's thought process should be like clay. Slow to dry. Malleable. This is because editing is a responsive endeavor, an interaction, as if engaging in a dialogue with the film itself. Good editors must learn how to listen carefully, because ultimately the film tells you how it needs to be made. Every film starts out as a faint pulse and ends up as a strong personality, confronting us with all the requisite pushes and pulls along the way: frustration, exhilaration, anxiety, pleasure, compromise. The best answers and solutions always lie within the material, are never imposed from without. Eventually and inevitably, the film will seem to ripen, gently whispering to the editor that it is time for closure, time to let the clay dry, Cinematic invention derives from the cauldron of this intense relationship.

For me, editing is an act of faith. I never really know where I'm going or how I'll get there. It's all trial and error. Sometimes a bad idea leads to a good solution. I make a commitment to a process of discovery. What catches my eye? What makes me laugh, cry, think? What matters and what doesn't? The more things you are capable of 'noticing,' the more potential connections there are to be made. I often think of editing in terms of chemistry, conjuring images and/or sounds as 'atoms,' having what a chemist would call 'valence,' or what the dictionary defines as the 'relative capacity to unite, react, or interact...combining power.' The combination of a specific sound with a specific image, or the juxtaposition of two images, becomes a kind of cinematic 'molecule,' itself capable or bonding with other sound/image, image/image, or even sound/sound units to form longer strings of molecules. They, in turn, can be combined to form more elaborate cinematic sequences, compounds of thought. Whether documentary, dramatic, or experimental, it's all a kind of chemistry.

The first 'molecule' I generated for my experimental short, Everywhere at Once (1985), was the sound of a xylophone juxtaposed over an aerial image of a red and white striped school bus passing under a lamp post. It was as if the lamp post was 'playing' the striped keyboard of the passing bus. This bit of cinematic magic suggested the possibility of creating an entire film -- a kind of miniature symphony -- collaged of similar music-to-image relationships, each one a unique discovery of a particular shot's 'valence' to a different isolated fragment of music.

My film, The Family Album (1986) utilized an enormous collection of 16mm American home movies (gathered from more than 75 different families) from the 1920s through the 1940s. I began to create juxtapositions of these images with various family audio recordings, including accounts of birthday parties, weddings, funerals, audio letters and oral histories. For instance, I combined a woman's voice saying, 'I always looked like I was happy to the public, but it just was never like that in the home,' over an image of a man and woman smiling and joking for the camera. Contradictory juxtapositions like this call into question the ways in which supposedly joyous images created for posterity reflect people's real inner lives and emotions. The Family Album is built entirely of voice-over sound to image 'discoveries,' each exploring a different aspect of the complicated universality of family life and its rituals. The 60-minute film is structured from birth to death, and weaves its elements into a composite lifetime: the celebrations and struggles along the path from childhood to adulthood, from innocence to experience.

My recent film, Intimate Stranger, was a biographical portrait of my grandfather, whose ambitions to write an autobiography was abruptly ended by his sudden death in 1974. At the time, thousands of his carefully preserved photographs, letters documents and journals -- the paper trail of his life -- were boxed up and put into storage. Fifteen years later, I began my search to 'discover' a form in which to somehow complete his unfinished autobiographical undertaking.

In retrospect it seemed so obvious. I would transform 'the typewriter,' tool of his autobiography, into a cinematic device. I would cast myself in the role of writer, as if continuing to tell his life story, metaphorically, on film. I would control the rhythms and sounds of the typewriter as a metrical and graphic framework for the images, creating an artificial order out of a seemingly formless abundance of personal documentation. This strategy allowed me to create various fluid or staccato montages of imagery, all rhythmically synchronized to the thuddy click/clack sound of a manual typewriter. Montage as a personal grammar. A kind of sculpting in time.

Every still photographic image in Intimate Stranger is 'typed' on and off. Every distinct source of visual imagery is punctuated with a specific audio-visual cue. When I get to the end of a specific period in my grandfather's life, a white horizontal bar moves left to right across the frame, signaled by the sound of a typewriter bell and accompanied by the sound effect of a typewriter carriage return. The following shot has the feel of a fresh clean page, a new chapter.

Depending upon the situation, I played the typewriter like an instrument, utilizing a wide range of 'musical' rhythms -- from delicate and emotional to fierce, pounding and angry. When Italian fascist soldiers were marching, I typed the sound for each one of their footsteps. When I used images of war, I typed the sound of each bomb explosion, a torrent of machine gun-like frenzy like actual sound effects.

In one emotionally charged sequence that occurs midway through the film -- a shot of my grandmother walking down the front steps of her house -- the image suddenly freezes. Another step. Freeze frame. A distinct typewriter key hit articulates the freeze frame for each of her six footsteps. At her final step, a voice-over says, "She had a nervous breakdown... Alan." Her solemn frozen image remains on the screen for two more seconds, allowing the emotional weight of this revelation to linger with the viewer.

In Intimate Stranger I choose to conduct interviews with family members, friends and business colleagues on audiotape rather than film them as 'talking heads.' The audio montage of these voice-over interviews was carefully composed, counterpointing and juxtaposing the various interview voices, their conflicting assessments, perspectives and memories of my grandfather. The dynamic interaction of these interview voices created the illusion of a communal audio space, a group discussion. Each interview was, of course, unique and independent of the other.

In many ways one might call Intimate Stranger a 'handmade' film. My presence as editor was tangible yet invisible, controlling but playful; the viewer feels my presence at the splicer 'typewriter,' an unseen hand behind the screen. For me, the greatest joy of making films is participating in the mysterious alchemy of the editing process. Day by day, shot by shot, frame by frame, gesture by gesture, the film gets better. It's a careful balance of patience and passion, a feeling I can't find any other place.

- ◻ Gathering Stones

- ✓ PATIENCE & PASSION

- ◻ TOP TEN FILMS (IDFA)

- ◻ WIDE AWAKE DIRECTOR'S STATEMENT

- ◻ LIKE MY FATHER BEFORE ME

- ◻ MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA

- ◻ ICE FISHING AND SKYWAYS

- ◻ OUTSIDE LOOKING IN

- ◻ ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION 20TH ANNIVERSARY

- ◻ WHY Alan Berliner WATCHES HIS FILMS WITH AN AUDIENCE EVERY CHANCE HE GETS