Gathering Stones

TO THE RESCUE: EIGHT ARTISTS IN AN ARCHIVE

AN EXHIBITION SPONSORED BY

THE AMERICAN JEWISH JOINT DISTRIBUTION COMMITTEE

FEBRUARY 1999

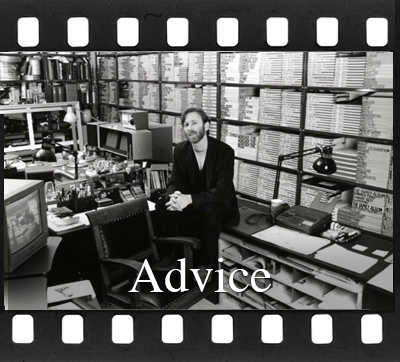

As both a filmmaker and a media artist-especially one who works a lot with found and appropriated materials-I'm always on the lookout for new and unusual audio and visual elements that I might someday find a way to work with. Over the years I've accumulated a rather elaborate personal archive, filled with many old photographs, films, slides, books, magazines, postcards, audio-tapes, record albums, videotapes, and other odds and ends. I’ve also gathered a small but special collection of old family photo albums. My primary sources for many of these things have been flea markets, junk shops and garage sales.

About twenty years ago I was living in the mid-west, and found myself one early Sunday morning at a garage sale in a typical suburban neighborhood. Scanning the usual assortment of miscellaneous household clutter, my eyes focused on an old family photo album. If I remember correctly, the price was ten or fifteen dollars, quite reasonable for an antique-looking if somewhat frayed collection of about 100 black-and-white photographs that appeared to have been taken sometime in the 1930s.

Eureka! A find. A steal. What a great way to start the morning. As I took the money out of my pocket, something made me ask the young girl behind the table, who in her own way seemed equally excited to be making her first sale of the day, if she knew anything about the album. She said she wasn't sure, but thought that it contained old pictures of people who in some way were related to her family.

In the midst of my glee -- wasn't I the perfect customer for this old book of images? I already had a collection of similar photo albums. I would protect it, treasure it, study it, and maybe even use it in a work one day. - I suddenly stopped short. Something felt wrong. It was one thing to purchase a photo album from flea market vendors or junk shop owners who salvage personal memorabilia from estate sales and other third party sources; it was altogether another to purchase one from the very family of its origin. Ethically. Aesthetically. I had a problem.

I asked the young girl if her parents were around and whether I could speak to one of them. When her mother finally came out, I gently implored her not to sell the album. Not to me. Not to anyone. Ever. I told her that one day, someone- her children, her grandchildren, her great-grandchildren, or some other relative-might ask about it, want to see it, would discover it no longer existed, and would deeply regret its loss. It was too precious to sell. I suggested that she just put the album away for now. She seemed to agree, half-heartedly chiding herself for making such a foolish mistake.

I left the garage sale with mixed emotions. I certainly felt a deep sense of relief that I had done the right thing, but I also had a queasy premonition that I had merely been indulged; that the album had probably gone right back for sale immediately after I left. To this day, when I look through the other family photo albums in my collection, I wonder what stories of indifference, ignorance, or tragic circumstances allowed them to become exiled and orphaned from their families of origin.

Within my own extended family, both maternal and paternal, I am the keeper of the memory-the family archivist, historian and guardian of virtually every important photograph and family document. I have done a great deal of research, had old photographs repaired and restored, foreign language documents and letters translated, and made everything available to any family member who expressed interest. If the truth be told, few if any ever have. But this personal family archive has led to the creation of my two most recent films, Intimate Stranger and Nobody's Business, each of which idiosyncratically explores a distinct half of my family heritage.

It feels like I've always had this impulse to collect. My uncle says I inherited what he mischievously calls "the saving gene" from my maternal grandfather. But it's important to note that I don't collect things with any intrinsic monetary value. I just save things in the service of my ongoing work, acting as a kind of bricoleur who gathers, accumulates, and assembles things, ideas, and meanings as he goes along. I do owe a debt of gratitude to my grandfather, whose weekly gift of postage stamps from all over the world helped establish my first image bank at the age of seven. My first private archive. Thousands of tiny little images. Photographs. Frames. I treasured them. Memorized them. Spent countless hours ritually organizing them. Landscapes. Languages. Colors. Icons. World leaders. Historical events. And on and on. Little did I know that I was teaching myself some of the crucial skills of filmmaking.

When I was invited to participate in this exhibition, it felt as if I had been preparing for it my whole life. The initial title for the exhibition read, "Artists in an Archive." Each of us was to make a journey into the Joint's photo collection, and navigate through a pool of images so extensive and varied that it still has yet to be fully catalogued. Like being let off at the edge of a vast wilderness without a map. I was told to immerse myself. In my own way and at my own speed. To dive in, through, up, over, and across. No rules. Just come up for air with the inspiration for a new work. This was music to my ears. And sounded familiar.

For instance, in 1986, I purchased a rather large collection of rare 16mm black-and-white home movies, representing some seventy-five different families of mixed racial, religious, ethnic, and class origins, taken from the mid-1920s through the late 1940s. I bought them from a lifelong cinemabilia collector who simply had no more room to store them. After spending close to a year studying the more than fifty hours of material, I began work on a film titled The Family Album, which ultimately became a complex collage of sounds and images, exploring the celebrations, struggles, conflicts, and contradictions of American family life. Like my collection of family photo albums, virtually every face in this sixty-minute film is anonymous, without a name or a story. Celluloid orphans.

By juxtaposing and counterpointing a wide range of intimate sounds - including found and donated recordings of oral histories, birthday parties, weddings, funerals, anniversaries, holiday gatherings, music lessons, audio letters, and just plain old fly-on-the-wall arguments in the kitchen - with hundreds of different home movie images, The Family Album gives the myriad nameless faces in the film new but provisional identities. And a strange kind of (cinematic) immortality.

To the extent that I understand it, my internal compass has always been calibrated by an intense kind of listening. Being attuned to the dialectical pushes and pulls, and an intuitive feeling for the boundaries-inside and outside-of whatever aesthetic territory I enter. When I first arrived at the Joint's photo archive, my first instinct (and compulsion) was to look at every single photograph. And indeed, over the course of many hours, days, and weeks, I did empty many shelves completely. Suffering the patience. Box by box. Folder by folder. Image by image. Taking notes along the way.

I never did get all the way through. Something stopped me. A memory. One afternoon, as I was pondering the weary smile on the face of an elderly Jewish man, I recalled something my father said to me in my film Nobody's Business when I showed him photographs of his Polish grandparents for the very first time. "He looks like another old Jew with a yarmulke! . . .That's all. . . . I have no emotional response. . . . They could be taken out of a storybook, I don't know them. . . . They mean nothing to me." He was saying that the faces of his grandparents were, in effect, generic. That without any specific history, experience, or memory to hold onto, they might as well have been strangers. Their reality as relatives, as people, as faces, and as photographic images was absolutely arbitrary.

Staring down at the growing pile of photographs in front of me made me realize that in some way my father was correct. Each of these anonymous faces could just as easily be my grandparents, great-grandparents, or some distant relative. They certainly looked the part. And for the Ashkenazi part of my heritage (I'm also half Sephardic), it's more than remotely possible that we are indeed somehow related. In fact, some genealogists estimate that most Jews of Eastern European descent are probably somewhere between eighth and twelfth cousins.

Reflecting further upon my father's cynicism allowed me to open up to these images. Every new face I came upon - man, woman, or child - whether melancholy, serene, youthful, wrinkled, strong, powerful, tired, or frail, began to resonate as a link to something I'd forgotten. Or never known. A lost culture. A vanished community. Became a bridge to Jewish history. A transcendent mirror for my own complicated assimilation as a late twentieth-century American Jew. Became family.

Somehow I had come upon an understanding of the Joint photo archive as a kind of collective "family album" of the Jewish people. For me, the intentional anonymity and open-endedness of the photographs in Gathering Stones, invites each viewer to invent his or her own way of measuring the distance between private and collective memory, between family member and stranger, between the living and the dead. By transforming the idea of a family photo album - a powerful emotional symbol of preservation and memory - into a site of commemoration, the anonymous images in Gathering Stones can become imbued with personal and mythic dimensions. Yes, indeed, my father was right. These people could be anybody. And they are.

- ✓ Gathering Stones

- ◻ PATIENCE & PASSION

- ◻ TOP TEN FILMS (IDFA)

- ◻ WIDE AWAKE DIRECTOR'S STATEMENT

- ◻ LIKE MY FATHER BEFORE ME

- ◻ MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA

- ◻ ICE FISHING AND SKYWAYS

- ◻ OUTSIDE LOOKING IN

- ◻ ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION 20TH ANNIVERSARY

- ◻ WHY Alan Berliner WATCHES HIS FILMS WITH AN AUDIENCE EVERY CHANCE HE GETS