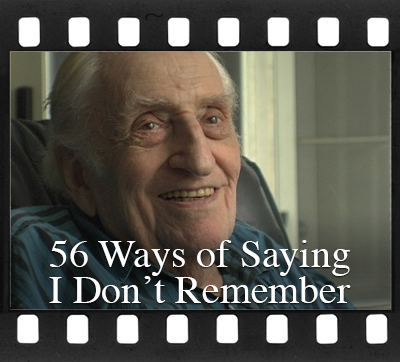

My father, Oscar Berliner died on August 19th, 2001 at 11:40pm

A funeral service was held at

Riverside Memorial Chapel

New York City

August 22, 2001

1:00 pm

Eulogy For

OSCAR BERLINER

Delivered by

Alan Berliner

The first thing I’d like to say is that if my father could be here at his own funeral to see so many people gathered on his behalf -- he’d think you were all crazy.

This is a pretty fancy funeral parlor for someone like my father. He was someone who had very simple tastes. Vanilla all the way. In fact this might very well be the most luxurious place he’s ever spent the night. I’m certain many prominent New Yorkers have been eulogized in this very room, which once again makes me reflect upon my humble father and imagine that if he were able to be here, the first thing he’d ask me would be, "how much do they get for this?"

And then tell me it’s not worth it.

But before I go on, I just want to confirm for those of you who’ve never been in my position, -- it’s true what they say -- no matter how much you think you’re prepared, you’re never ready when it actually happens.

Well, obviously my father wasn’t a prominent New Yorker, and no one will be reading his obituary in today’s newspaper, but it just so happens that this ordinary citizen of New York City did have his very own biographer. In a few short years, I probably asked him more questions than most people get asked in a lifetime.

I certainly learned a lot about him. But I also learned a lot from him.

Observing my father over the years taught me to see every life as an equation. An equation that each of us attempts to solve as we move through the ups and downs of our respective journeys. In retrospect, every time I stop to think about the circumstances of his life, the complexity of his predicament -- how my father chose to solve his own equation -- I sit in total awe at the sheer amount of energy it took for him to make it through each and every day.

First there was the brain tumor back in the mid 1960’s -- a time before cat scans and MRI’s. Most people don’t know that the surgeons never actually took out the entire tumor. That my father was forced to make a decision between having it totally removed or being disfigured on the right side of his face for the rest of his life. It must have been nightmarish for him to know that there was a tumor growing ever so slowly inside his head all these years.

That brain surgery left him permanently deaf in one ear. The severe hearing loss in his other ear was just genes -- "a gift from his mother’s side of the family," as he would say.

Now that you know he was virtually deaf, I feel pretty secure in being able to say anything I want to about my father right now, because even if he was here with us, he wouldn’t be able to hear me anyway.

His hearing disability was the big "X" factor in his equation. It kept him from being social. From making friends. From talking to people about the weather. Or the score of the Met game. Or how cute his granddaughters were. It kept him isolated. It made him a cave dweller.

I can’t remember the last time he went to a movie. Maybe 30 years ago. He didn’t -- because he couldn’t — ever listen to the radio. Hardly ever watched television. Never ever participated in any activities offered by the community center, the senior citizen residence or the nursing home. Never.

And for the record, it took me five years to finally convince him to try on a hearing aid.

At some point I realized that he had stopped reading. Books. Magazines. Even newspapers. And once again, after a great deal of resistance -- because my father was terrified of doctors -- he finally allowed me to take him to an eye doctor.

That’s when I learned that he was blind in one eye. Apparently unchecked glaucoma had destroyed the optic nerve in his right eye and was closing in fast on the left. I won’t deny how furious I was with him.

Why didn’t he tell me or Lynn that he was having trouble seeing?

How could we help him if he wouldn’t communicate with us?

And then it dawned on me.

His vision problem, like his hearing loss was just another burden to overcome.

He simply absorbed it into the equation of his life.

With a silent pride.

About eleven years ago he had another brain operation, this time to remedy a condition called hydrocephalus, -- or water on the brain -- which caused him to lose his balance. Eventually he couldn’t walk without holding on to walls, furniture or a companion’s arm. In the last years of his life, even a cane wasn’t much help and so he started wheeling a shopping cart wherever he went. If anyone asked, he pretended he was going shopping.

Even in the very last days of his life, lying in the hospital bed in what must have been enormous agony because of a broken hip, he never complained about the pain or discomfort. I can only imagine that he had internalized it, conquered it as yet another obstacle to overcome in his heart wrenching saga.

And then there was his isolation. My father the recluse. The thinker. Brooding over his divorce. Pondering the fear of being the last of eleven brothers and sisters. Worrying about his children. Who knows? Over the years, I’d always hoped and imagined somehow, -- all alone inside his room every day — that he had a secret life, that maybe he was keeping a secret diary. I would have been thrilled just to hear that he was spending all his time collecting bottle caps. Or match books. Or straws from the cafeteria. Anything.

But no. My father lived his life mostly inside his own head. A head that throbbed with headaches almost every day of his adult life. A headache that eluded doctors, x-rays, cat scans, MRI’s and every version of pain-killer known to mankind. Announcing his daily headache was my father’s way of saying hello. Sometimes he said it before we even kissed hello.

They had my father in mind when they invented the word stoic. He was the prototype. He never complained about the next curve ball life threw his way. Life was suffering and he was good at it. Life was a boxing match and he could take a punch with the best of them.

Now please don’t think I’m being too hard on him. What I’m really talking about is my utter amazement at the incredible strength that it took to be Oscar Berliner. His courage. His refusal to surrender. He was the most stubborn son of a gun you ever met. With a will of steel. Underneath, and despite his sadness, the man had a life force second to none.

At the same time, you couldn't meet my father and not wonder why he couldn’t just put his tremendous energy and spirit into utilizing -- into celebrating -- all the things he had going for him. And he did have many gifts. He was smart. I’m sure he would want me to tell you that he skipped two grades in school growing up. He was handsome. He was told more than once that he looked like Tyrone Powers or William Holden, though frankly I though he was more handsome than both of them. He was incredibly sensitive and gentle. And humble to a fault. And he could be charming. Real charming. They tell me he wasn’t just a good salesman, he was a great salesman.

How do you explain someone with such great people skills, who chooses to remain so all alone most of the time?

But it was impossible not to love this man.

And speaking of love, I wasn’t the only one crying the night he received a standing ovation at Alice Tully Hall after the premiere of Nobody’s Business -- watching him like an innocent deer, caught in the glare of generous applause and love from 1100 warm hearted strangers. It was perhaps the most emotional moment of my entire life, and though he never told me personally -- I had to hear it from someone else a few weeks later -- the happiest night of his life too.

In all the years following Nobody’s Business, he claimed he would never get a swell head from all the attention he received, if only because after all his brain operations, there wasn’t anything left to get swollen. Later on after his dementia set in, I used to love it when he’d introduce himself to other patients in the nursing home as a movie star. Of course, he could never hear their incredulous responses, but he did see their smiles. And though I must have told him a thousand times, he never really connected with -- or appreciated -- the fact that people all over the world always ask about him, some of them claiming that he’s a little bit a father to everyone who’s had a chance to see the film.

In the end, my father’s gift to me and Lynn -- is like my father himself -- a series of subtle contradictions. By needing our help in navigating through the world…

translating for him,

interpreting for him

hearing for him

seeing for him

helping him walk

shopping for him

defending him

comforting him

watching his back

he taught us the meaning of compassion, and pushed us towards a higher wisdom in accepting the stresses and obligations of that intimate contract known as family.

Watching my father cope with the demands of his mental and physical fragility taught me and Lynn what it means to be strong. The absolute power of perseverance.

And finally, sharing the joys and sorrows of helping my father struggle to make sense of his life’s equation has made us as close as a brother and sister can ever hope to be, and enabled us to understand the transcendent source of unconditional devotion and loyalty,

which is,

of course,

love.

He was my sparring partner, my leading man,

The undisputed heavyweight champion of my world.

And I’m gonna miss that feisty son of a XXXXX until the end of my days.

From the bottom of my heart, I thank you all for being here.

- ◻ SYNOPSIS

- ◻ AWARDS

- ◻ FESTIVALS & SCREENINGS

- ◻ WARSHAWSKI ARTICLE

- ◻ RENOV LECTURE

- ◻ NYU - DEC. 5TH, 2010

- ◻ STRANGER THAN FICTION - FEB 12TH, 2011

- ◻ SELECTED REVIEWS

- ◻ PRESS QUOTES

- ◻ JOURNAL EXCERPTS

- ◻ POV Interview

- ✓ EULOGY FOR OSCAR BERLINER

- ◻ CREDITS

- ◻ MEDIA COVERAGE

- ◻ VIEW CLIPS

- ◻ PHOTOS